“The heresy of heresies was common sense”

George Orwell (1903-1950), real name Eric Blair, was one of the most important English political writers of the 20th century.

He challenged totalitarianism in all its forms and, in opposition to its machine-like brutality, put forward a vision of life based on simplicity, authenticity and moral decency.

Orwell was a libertarian socialist, close to the anarchist movement, and often criticised, from within, the failure of the left to attract the widespread public support which its principles deserved.

He feared that its basic call for justice and liberty had been buried under layers of sterile dogma, boring Marxist jargon and blinkered enthusiasm for industrial “progress”.

The result, he feared, was that people like himself would recoil from this debased left and fall into the ideological arms of Fascism, which sought to gain power by selling the public its own distorted version of socialism.

The result, he feared, was that people like himself would recoil from this debased left and fall into the ideological arms of Fascism, which sought to gain power by selling the public its own distorted version of socialism.

Orwell learnt his politics from life rather than from textbooks. He learned hatred of British imperialism from his years in Burma, he learned the harsh realities of capitalist society from his spells of semi-voluntary poverty in Paris and London; he learned his distrust of Stalinist Communism from fighting in Spain; he learned about state propaganda from working at the BBC.

Although Orwell revelled in the apparent contradictions in his world view, and detested “the smelly little orthodoxies” (1) of fixed systems of thought from Catholicism to Communism, his instincts were always defiantly left-wing and anti-authoritarian.

In 1936, he told Philip Mairet he was going to Spain. When asked why, he simply replied: “This fascism. Somebody’s got to stop it”. (2)

An account of a night attack against Franco’s forces on the Aragon Front the next year described “Eric Blair’s tall figure coolly strolling forward through the storm of fire”. (3)

Orwell/Blair wrote in Homage to Catalonia: “I have no particular love for the idealized ‘worker’ as he appears in the bourgeois Communist’s mind, but when I see an actual flesh-and-blood worker in conflict with his natural enemy, the policeman, I do not have to ask myself which side I am on”. (4)

After his experiences on the Iberian peninsula he became distrustful of any anti-fascist struggle that was not also a revolutionary struggle against capitalism.

He wrote in a letter: “After what I have seen in Spain I have come to the conclusion that it is futile to be ‘anti-Fascist’ while attempting to preserve capitalism. Fascism after all is only a development of capitalism, and the mildest democracy, so-called, is liable to turn into Fascism when the pinch comes…

“If one collaborates with a capitalist-imperialist government in a struggle ‘against Fascism’, ie. against a rival imperialism, one is simply letting Fascism in by the back door”. (5)

Orwell was persuaded by Emma Goldman to join the International Anti-Fascist Solidarity Committee where he came into contact with anarchists such as Herbert Read and John Cowper Powys. He was also friends with the anarchists Marie Louise Berneri and George Woodcock.

He supported the war against Hitler in the hope that it would lead to revolution and joined the Home Guard which he saw, for a while, as potentially a revolutionary popular militia like the New Model Army of the 17th century.

After the war ended, Orwell joined the libertarian Freedom Defence Committee and contributed to the anarchist journal Freedom.

But alongside his natural left-wing allegiance was something which was regarded, at the time, as somehow in contradiction with all that – a deep love for traditional ways, for old England and above all for nature.

Bernard Crick describes how Orwell was both “tender towards nature” and alarmed at “the suburban sprawl over the countryside”. (6) He adds: “Orwell thought that man should be as one with natural objects. Like Rousseau, he disliked the artificiality of the city”. (7)

George Woodcock writes that Orwell was motivated by a “nostalgia for a simpler and cleaner way of life which emerges so poignantly in Coming Up for Air and even gives pathos to parts of Nineteen Eighty-Four“. (8)

He had an “essentially naturalistic attitude” (9) and took great joy from contact with nature: “He fed from the earth, like Antaeus, and his happiest recollections of youth, like his happiest letters, were concerned in some way or another with rural experiences”. (10)

Orwell was particularly outspoken in his condemnation of industrial society in The Road to Wigan Pier. He wrote: “It is only in our own age, when mechanization has finally triumphed, that we can actually feel the tendency of the machine to make a fully human life imposssible”. (11)

Orwell was particularly outspoken in his condemnation of industrial society in The Road to Wigan Pier. He wrote: “It is only in our own age, when mechanization has finally triumphed, that we can actually feel the tendency of the machine to make a fully human life imposssible”. (11)

“The question one has got to consider is whether there is any human activity which would not be maimed by the dominance of the machine”. (12)

He decried the way that it was becoming difficult to imagine any way out of the machine world, as people’s preferences and habits became defined by its norms: “Mechanization leads to the decay of taste, the decay of taste leads to the demand for machine-made articles and hence to more mechanization, and so a vicious circle is established”. (13)

George Bowling, the central character in Coming Up for Air, has a glimpse of all this when he tastes a frankfurter in a 1930s Milk Bar in central London: “It was fish! A sausage, a thing calling itself a frankfurter, filled with fish! It gave me the feeling that I’d bitten into the modern world and discovered what it was really made of.

“That’s the way we’re going nowadays. Everything slick and streamlined, everything made out of something else. Celluloid, rubber, chromium-steel everywhere, arc lamps blazing all night, glass roofs over your head, radios all playing the same tune, no vegetation left, everything cemented over, mock-turtles grazing under the neutral fruit-trees.

“But when you come down to brass tacks and get your teeth into something solid, a sausage for instance, that’s what you get. Rotten fish in a rubber skin. Bombs of filth bursting inside your mouth”. (14)

Orwell expressed particular despair at the way in which socialism, influenced by rigid Marxist materialism and Soviet industrialism, had failed to oppose the “swindle of progress”. (15)

Worse than that, it had even reached the fanatical point at which “all sentiment for the past carries with it a vague smell of heresy”. (16)

Most socialists regarded with contempt the traditional beliefs and ways of life that held together pre-industrial organic community and wanted to steamroller the past to build the new scientifically-planned, efficient concrete-communist future.

Orwell remarked: “The unfortunate thing is that Socialism, as usually presented, is bound up with the idea of mechanical progress, not merely as a necessary development but as an end in itself, almost as a kind of religion”. (17)

He feared that “revulsion from a shallow conception of progress” could drive people away from socialism into the hands of the Fascists – as it already had, he argued in a BBC talk, with Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. (18)

At the same time, Orwell feared that lurking behind the “urban creed” (19) of socialism was “a hypertrophied sense of order”. (20) This meant that even his own ideology, English socialism, was in danger of turning into the fascistic IngSoc of his fictional dystopia.

At the same time, Orwell feared that lurking behind the “urban creed” (19) of socialism was “a hypertrophied sense of order”. (20) This meant that even his own ideology, English socialism, was in danger of turning into the fascistic IngSoc of his fictional dystopia.

His two most famous warnings against totalitarianism, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, were both influenced by his experience of Communist propaganda in Spain, which had spread the total lie that the Trotskyites of POUM and their fellow anarchist revolutionaries were in fact “Fascists” working secretly for Franco.

One young man, Stafford Cottmann, who had fought fascism with POUM alongside Orwell, returned home to the UK only to have his home picketed by local Communists denouncing him as a “Fascist”. (21)

Crick remarks: “It is still hard to recall how vile, gross and fabricated such propaganda was. Orwell saw before his own eyes not merely the distortion of evidence through differing perspectives but the sheer invention of history. One aspect of Nineteen Eighty-Four was already occurring”. (22)

When Orwell encountered the same attitude to truth in the wartime BBC, where he worked, he realised that a dangerous modern tendency was revealing itself, in which truth became secondary to control and the pursuit of power.

Explaining in 1949 why he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four, he explained that “totalitarian ideas have taken root in the minds of intellectuals everywhere, and I have tried to draw these ideas out to their logical consequences”. (23)

Explaining in 1949 why he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four, he explained that “totalitarian ideas have taken root in the minds of intellectuals everywhere, and I have tried to draw these ideas out to their logical consequences”. (23)

This totalitarianism was in fact happening at a deeper level than the political surface, in the very way that intellectuals were starting to think: a way that reflected the artificiality and separation from natural reality of the industrial age.

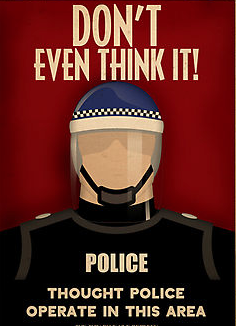

In the novel, Ingsoc’s Big Brother dictatorship has established near-complete control of the population not merely on a physical level, but on a psychological one too – it is able to manipulate the experience of those it dominates, by denying the possibility of any objective reality.

“Not merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality was tacitly denied by their philosophy. The heresy of heresies was common sense… If both the past and external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable – what then?” (24)

Winston Smith’s struggle to keep a grip on objective reality, to know that two plus two makes four whatever the ideological demands of the Party, is a central theme of Orwell’s novel.

The character tells himself: “Truisms are true, hold on to that! The solid world exists, its laws do not change. Stones are hard, water is wet, objects unsupported fall towards the earth’s centre”. (25)

The Big Brother system has invented a new language which controls people’s minds by making heretical ideas impossible to even formulate.

One of the Party members developing Newspeak tells Smith: “You think, I dare say, that our chief job is inventing new words. But not a bit of it! We’re destroying words – scores of them, hundreds of them, every day”. (26)

He explains: “Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thought-crime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it… By 2050 – earlier, probably – all real knowledge of Oldspeak will have disappeared. The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed”. (27)

In the face of this truth-denying dogmatism, Orwell insisted that any authentic radical should always remain free to reject the dominant official ideology: “He should never turn back from a train of thought because it may lead to a heresy, and he should not mind very much if his unorthodoxy is smelt out, as it probably will be”.

While co-operating with others to some extent, a free-thinking radical had to fight the capitalist system “as an individual, an outsider, at the most an unwelcome guerilla on the flank of a regular army”. (28)

In Woodcock’s words, Orwell was “a good and angry man who sought for the truth because he knew that only in its air would freedom and justice survive”. (29)

Video links: Nineteen Eighty-Four. TV film from 1954. (1hr 47 mins). Orwell’s 1984 Summary, (8 mins).

1. George Woodcock, The Crystal Spirit: A Study of George Orwell (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970), p. 51.

2. Bernard Crick, George Orwell: A Life (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1982), p. 312.

3. ‘Night Attack on the Aragon Front, The New Leader, 30 April 1937, p. 3. cit. Crick, p. 327.

4. George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964), p. 119.

5. Crick, p. 350.

6. Crick, p. 272.

7. Crick, p. 301.

8. Woodcock, pp. 34-35.

9. Woodcock, p. 56.

10. Woodcock, p. 55.

11. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), p. 167.

12. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 172.

13. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 180.

14. George Orwell, Coming Up for Air (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963), pp. 26-27.

15. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 178.

16. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 177.

17. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 166.

18. Crick, p. 430.

19. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 164.

20. Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 157.

21. Crick, p. 344.

22. Crick, p. 334.

23. Letter to Francis A. Henson, 16 June 1949, cit. Crick, p. 569.

24. George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (New York: Signet, 1950), p. 80.

25. Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, p. 81.

26. Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, pp. 50-51.

27. Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, pp. 52-53.

28. Woodcock, p. 220.

29. Woodcock, p. 278.